Kangaroos

Kangaroos are native animals who have adapted uniquely to the Australian landscape. Their ancient ancestor has been traced back 24 million years to the Palaeopotorous – the starting point of all known kangaroo species.

Kangaroos are social animals who live in large groups called mobs. Mothers and joeys (young kangaroos) form close bonds and communicate with each other using unique calls. 1 Studies show that female Eastern Grey kangaroos recognise the individual voices of their young, and mothers and daughters maintain long-term bonds.

What is the Commercial Kangaroo Industry?

The Australian commercial kangaroo industry is a multi-million dollar industry. Kangaroo meat and skins are used to create a range of products, including pet food, meat for human consumption and kangaroo leather. Each year, approximately 4,000 tonnes of kangaroo meat for human consumption is exported to countries around the world.

Commercial ‘harvesting’ (shooting) is permitted for four species of kangaroo in Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia and South Australia, and two species of wallaby in Tasmania.

Annual harvest quotas are set based on kangaroo population estimates, which determine the maximum number of kangaroos that can be harvested in that year. The quotas are referred to as ‘sustainable harvest quotas’, as they are set at a level intended to ensure conservation of kangaroo populations.

However, some scientists argue that there are issues with the methodologies used to determine these population estimates, placing into question the sustainability of the quotas.

Voiceless, animal protection advocates, and scientists, have also raised concerns regarding animal welfare issues in the industry (see discussion below).

What is Non-Commercial Kangaroo Hunting?

Non-commercial kangaroo hunting refers to the lawful shooting of kangaroos, without selling their meat or skins for profit. Government culling of kangaroos for conservation purposes is an example of non-commercial kangaroo shooting.

RSPCA Australia state that ‘[t]he general opinion given by those associated with kangaroo management is that there is a far higher degree of inhumane killing of kangaroos in non-commercial killing than with commercial killing’.

In some circumstances, there are non-lethal kangaroo management alternatives available, including translocation and fertility control.

Why Does Australia Allow Kangaroo Hunting?

Australian governments support non-commercial kangaroo hunting due to a belief that kangaroos are overpopulated in certain areas. They view kangaroos as pests that need to be controlled in order to maintain ecological balance and reduce impacts on agricultural land.

This belief has in part led to the establishment of the commercial kangaroo industry, enabling kangaroo meat and skins to be utilised as profitable ‘resources’ by industry, thereby facilitating population reduction. The Australian Government supports the commercial kangaroo industry, viewing it as a sustainable and profitable industry providing jobs for Australians.

Voiceless and other animal protection advocates challenge these ways of conceptualising kangaroos, questioning their classifications as ‘resources’ and ‘pests’.

Are Kangaroos ‘Pests’?

Despite being a native animal, many farmers consider kangaroos to be ‘economic’ pests because kangaroos break fences and are perceived to compete with their cattle and sheep for resources.

According to THINKK (the think tank for kangaroos), multiple studies show that kangaroos do not compete with livestock for food resources (except during drought) and kangaroo populations are not dependent on artificial watering points. Moreover, kangaroos have a small fraction of the energetic requirements (the need for food and water) of livestock.

A 2004 report by the Cooperative Research Centre for Pest Animal Control found that the estimated annual cost incurred by farmers due to kangaroos should be revised down from $200 million to $44 million, or $1.67 per kangaroo per year.

Animal protection advocates also raise broader issues with the use of the term ‘pest’ to describe any sentient animals, as it suggests that the lives of these animals are inherently less valuable than others.

How Are Kangaroos Killed?

Kangaroos are not farmed for their meat and skins. They are shot in the wild at night when they are most active, in generally rural and remote areas of Australia.

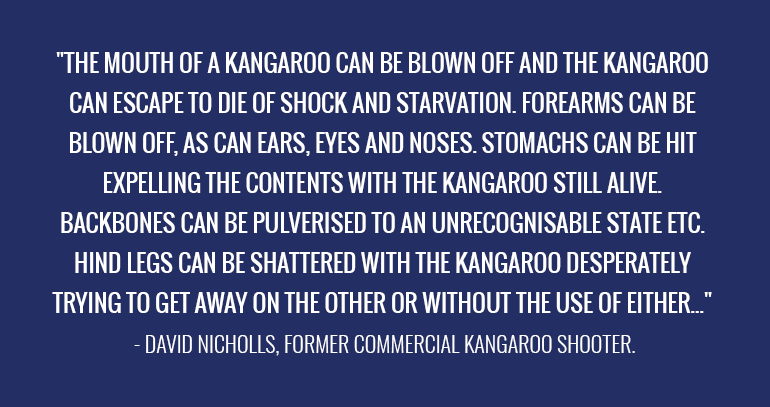

While shooters are required to abide by Commercial and Non-Commercial Codes of Practice which require them to aim for the brain to achieve instantaneous loss of consciousness, many factors affect their ability to achieve this.

Factors include impaired vision due to darkness and distance, weather conditions, the small target size of a kangaroo’s head, unexpected movements of startled kangaroos, and the skill and experience of the individual shooter.2

Accordingly, non-fatal body shots are an inevitable and unavoidable part of the industry, with the potential to cause painful injuries, prolonged suffering and a slow death.

Due to limited monitoring, it is difficult to establish accurate figures for the numbers of kangaroos who are mis-shot and wounded each year.

One method for trying to ascertain the number of mis-shot kangaroos is to examine carcasses in meat processing plants and chillers. Data collected from meat processing plants by RSPCA Australia in 2002 suggested that 4% of kangaroos were mis-shot, whilst an Animal Liberation NSW study examining chillers suggested that 40% of kangaroos may have been mis-shot.3 The Animal Liberation study examined whether the head was removed at the occipital joint, which may indicate that the kangaroo was shot in the neck rather than the head.

However, the precise number of mis-shot kangaroos can not be ascertained using these methods as commercial shooters are not paid for body-shot kangaroos, and therefore do not bring them to processing facilities.

Accordingly, although we know that wounding definitely occurs, we do not know exactly how many kangaroos are wounded as a result of the commercial kangaroo industry each year.

How is Compliance With the Code Monitored and Enforced?

State governments are primarily charged with ensuring that compliance with the Code is monitored and enforced. However, monitoring is particularly difficult in this context due to the fact that kangaroo shooting occurs at night across varying rural locations.

Although some inspections in the field do occur, there are no consistent regular inspections of all shooting locations. Boom et al argue that ‘[t]he lack of consistent and uniform inspections presents the most significant gap in the regulatory activity within the kangaroo industry’.4

Without inspections at the point of kill, it is very difficult to ensure that shooters are in full compliance with the Code.

A further issue is the fact that shooters are not required to retain the heads of kangaroos they have shot, making it challenging for authorities auditing these facilities to confirm whether they were killed by a direct shot to the head (as mandated by the Code) or a neck shot.

Why Are Joeys and Young-At-Foot Killed?

According to the Code of Practice for non-commercial shooting, shooters should avoid shooting female kangaroos where it is obvious they have dependent young. However, this guidance in the Code is not mandatory, and shooters are not expressly prohibited from shooting kangaroos with pouch young/young-at-foot. This guidance is not provided in the Code of Practice for commercial shooting.

As joeys can’t survive without their mothers, shooters must euthanase the joeys of killed females. Joeys left in their mother’s pouches, or alone in the bush, are likely to die from exposure, starvation or predation.

Shooters are required to employ specific euthanasia methods stipulated under the relevant Code. Under the Code for non-commercial shooting, small furless pouch young must be killed using a ‘single forceful blow to the base of the skull’ or ‘stunning, immediately followed by decapitation’. For furred pouch young, a ‘single forceful blow to the base of the skull’ must be used. Young-at-foot who have left the pouch must be killed with a ‘single shot to the brain or heart where it can be delivered accurately and in safety’.

Under the Code of Practice for commercial shooting, unfurred pouch young that are less than 5cm must be killed by decapitation or cervical dislocation, and those greater than 5cm must be killed by decapitation. Furred pouch young must be killed by a ‘concussive blow to the head’. Young-at-foot less than 5kg must also be killed by a concussive blow to head, and those larger than 5kg must be killed by a shot aimed at the head or chest.

Due to a lack of comprehensive in-field oversight, it is not possible to definitively state how many joeys are killed each year as a result of the commercial kangaroo industry. However, on a 10 year average, it is estimated that 800,000 dependent joeys are killed as collateral damage of the industry annually.5

It is also not possible to determine exactly how all joeys are killed in the field by shooters, and whether the methods of euthanasia used in practice are in compliance with the Code requirements.

Welfare issues are also created when shooters fail to euthanise joeys, who are unable to survive on their own in the wild. In 2014, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation published a report which found that although kangaroo shooters ‘report a strong intention to euthanase young-at-foot…this happens only rarely…’

Will There be a Ban on Killing Female Kangaroos?

Limited monitoring of compliance with the Code leaves open the possibility that dependent young will either be euthanised inhumanely, or not euthanised at all (leaving them vulnerable to death via predation or starvation). RSPCA Australia are of the view that a complete prohibition on shooting female kangaroos may be ‘the only solution to totally avoid the potential of cruelty to pouch young’.

The industry itself has begun to move away from female kangaroo shooting. In 2013, the Kangaroo Industries Association of Australia introduced a policy encouraging industry transition to a male-only take. Since that time, they report that ‘the level of females taken have declined from 30% of the overall take to less than 5% (NSW 2014, Qld 2015)’.

The Code of Practice for commercial shooting was reviewed in 2020. The revised Code failed to implement a prohibition on female kangaroo shooting, instead detailing more specific methods for killing dependent young. For example, in relation to euthanasia of partially-furred to fully-furred pouch young, the revised Code states (inter alia):

To deliver the concussive blow, carefully remove the young from the pouch (note they are not permanently attached to the teat at this stage of development but could still be suckling), hold the young firmly by the hindquarters (around the top of the back legs and base of tail) and then swing firmly and quickly in an arc so that the rear of the joey’s head is hit against a large solid surface that will not move or compress during the impact (e.g. the tray of a utility vehicle).

DO NOT hit the joeys’ head against the railing of the utility rack, as this can result in decapitation rather than the intended concussive blow to the head.

DO NOT suspend joeys upside down by the hindquarters or tail and then try to hit the head with an iron bar (or similar). Holding them in this manner allows the joey to move around and makes it difficult to make contact with the correct location on the head. In addition, the force of the blow may not be sufficient to render the joey unconscious with only one strike.

Accordingly, it is unlikely that a prohibition on female kangaroo shooting will be achieved in the near future, given the revision of the commercial Code took 12 years since the first edition.

Why is the Perspective of First Nations Culture Key to Kangaroo Protection and Advocacy?

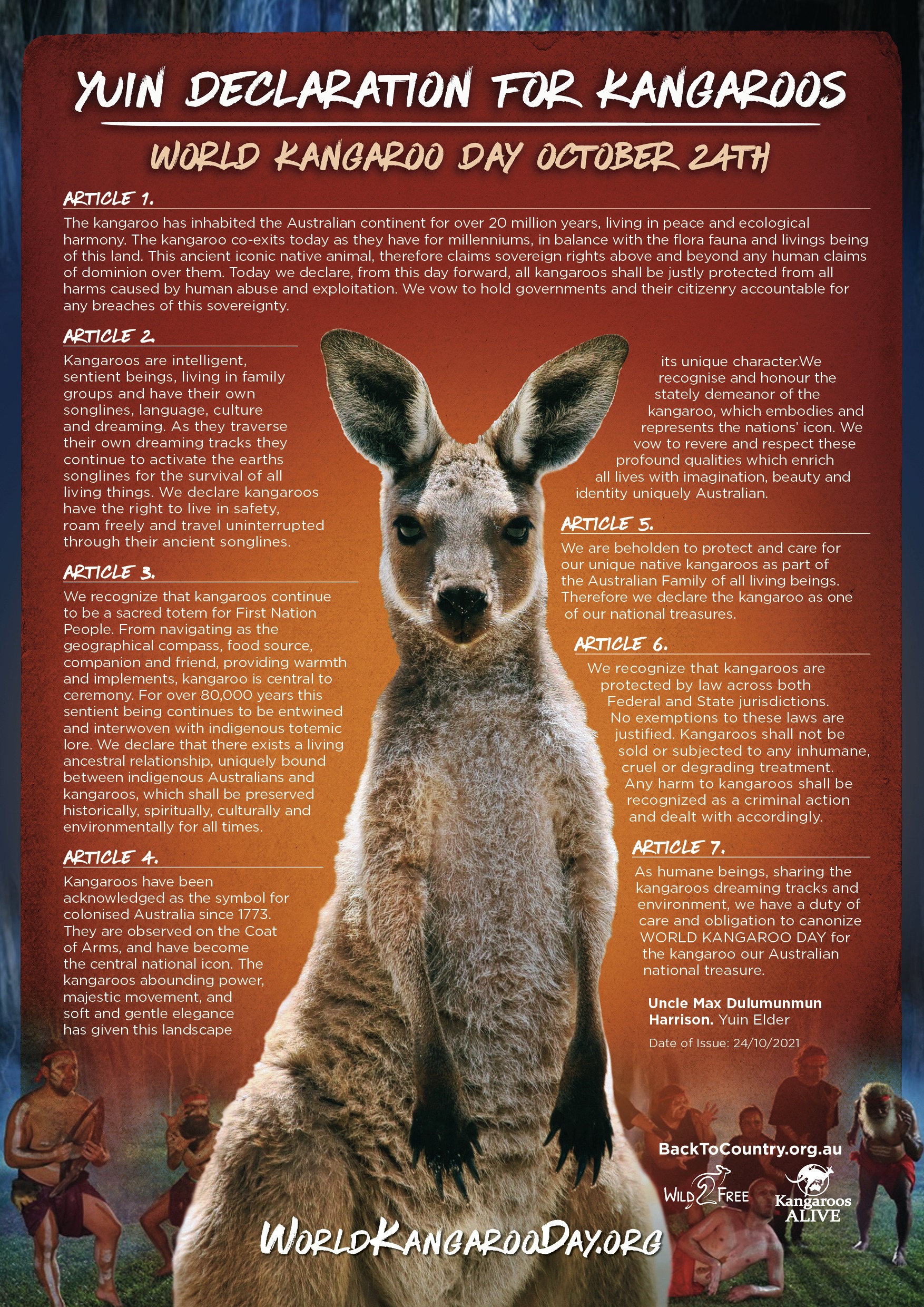

Kangaroos hold deep cultural, social, and spiritual significance to First Nations people. They are teachers, a Totem, food source, and are also part of ceremony. Unfortunately, the commercial kangaroo slaughter industry largely disregards and excludes the concerns of First Nations people and the cultural significance these native animals hold.

Kangaroos are a Totemic Species to many First Nations people. In Indigenous teachings, a Totem is a plant, animal, or other object that is inherited by members of a Clan, Mob, or Family as their spiritual emblem. These Totems are ancestors, and the link to story & knowledge, and responsibility for that Totem means restrictions upon hunting or using the animal as such.

In 2021, the NSW State Parliament held an inquiry into the health and well-being of kangaroos and other macropods in NSW, where experts from science, research, law, education, and First Nations culture provided evidence and insights on this issue. A key recommendation from the inquiry was for the government to undertake extensive and genuine consultation with First Nations peoples to seek their views regarding the commercial and non-commercial killing of kangaroos.

Three First Nations people were witnesses in the parliamentary inquiry, including the late Yuin Elder, Uncle Max, who worked tirelessly in his 85 years to protect and defend kangaroos. He spoke from the heart in his testimony about the interconnection of the iconic kangaroo and First Nations culture:

“The kangaroo preceded our Indigenous culture more than 80,000 years ago and deserved both the land and living rights above all other introduced species, the right to live without cruelty and exploitation… This powerful, soft-footed animal that shares our nation with us has been relegated last, replaced by the hard-hooved introduced animal species, creating displacement and desecration.”

“Inside cultural practice, we only took whatever was needed for food and medicine. We never harvested meat or medicine for profit. It is not spiritual practice to kill our iconic animals for $80 million per annum.” ~ Uncle Max, Yuin Elder

To build a co-existence program for kangaroos and educate communities about the First Nations connection to kangaroos and Country, Uncle Max presented a manifesto on World Kangaroo Day in 2021 on the rights of kangaroos to live free from exploitation and disrespect, called the Yuin Declaration. It outlines the complex interconnection between Kangaroos, Country and Aboriginal culture and spirituality and vows to hold governments and their citizens accountable for any breaches of this sovereignty.

What is Voiceless Doing to Help Kangaroos?

Voiceless is at the forefront of kangaroo advocacy in Australia and around the world, calling for an end to the commercial kangaroo industry.

Through the Voiceless Grants program (2004-2017), Voiceless supported numerous projects raising awareness of kangaroo welfare and the commercial kangaroo industry, including:

- The Australian Wildlife Protection Council’s ‘Kangaroo Trail’;

- On-the-ground investigations into kangaroo shooting;

- An analysis of kangaroo meat by the Australian Animal Justice Party;

- Reports and books exploring the myriad animal welfare issues raised by kangaroo shooting.

The Voiceless Grants Program, from 2023 onwards, will continue its support of kangaroo advocacy, focussing on people and projects that educate communities about the First Nations’ connection with kangaroos and Country and building stronger links between the First Nations community and kangaroo advocacy groups.

Voiceless has also supported the development of scientific and legal research on the issue. Directors Dr Dror Ben-Ami and Dr Dan Ramp co-founded THINKK – the Think Tank for Kangaroos. As a science-based research centre at the University of Technology, THINKK fostered understanding amongst Australians about kangaroos through critically reviewing the scientific evidence underpinning kangaroo management practices and exploring non-lethal management options consistent with ecology, animal welfare, human health and ethics. Voiceless similarly supported the founding of the Centre for Compassionate Conservation (CfCC) in Australia.

Voiceless is now raising awareness of these issues outside Australia, working closely with numerous prominent EU non-government organisations through membership with Eurogroup for Animals. We also regularly deliver presentations at universities across Australia, highlighting the inadequacies of the laws and policies governing kangaroo welfare.

Learn More

- Read the full transcript from the NSW State Parliament Inquiry into the Health and Wellbeing of Kangaroos and Other Macropods in New South Wales, 15 June 2021.

- Read more about the YUIN Declaration for Kangaroos.

- Watch the ground-breaking 2018 documentary, Kangaroo: A Love Hate Story, proudly supported by Voiceless.

- Read an open letter from various NGOs, including Voiceless, urging decision-makers to consider the conservation, animal welfare and health risks caused by the commercial and non-commercial kangaroo shooting industries.

- Access comprehensive resources from THINKK, the think tank for kangaroos.

- Read our 2019 submission to the Public Consultation on the Revised Kangaroo Harvesting Welfare Code of Practice.

- Read the 2012 report from THINKK, ‘Kangaroo Court: Enforcement of the law governing kangaroo killing’.

- Read the article ‘Kangaroos: Pest or Precious?’ on the Voiceless Blog by Bee-Elle, wildlife photographer and conservationist.

- Watch the 2012 Voiceless Animal Law Lecture Series presentation on the kangaroo industry by Keely Boom, previously a research fellow with THINKK, and an expert in animal law and environmental law.

Last updated December 2023

- C Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe, Life of Marsupials (CSIRO Publishing, 2005) 329.

- David Nicholls, ‘The Kangaroo – Falsely Maligned by Tradition’ in Maryland Wilson and David B. Croft (eds), Kangaroos Myths and Realities (Australian Wildlife Protection Council, 3rd ed, 2005), 38.

- Ben‐Ami D, Boom K, Boronyak L, Townend C, Ramp D, Croft D, Bekoff M, ‘The welfare ethics of the commercial killing of free-ranging kangaroos: an evaluation of the benefits and costs of the industry’ (2014) 23 Animal Welfare 1, 5. The difference in the RSPCA Australia and Animal Liberation NSW estimates is due to differences in sampling methodology. Animal Liberation NSW sampling was based on whether the head was severed at or below the atlantal-occipital joint, which is reportedly the most efficient point to sever a kangaroo’s head. RSPCA sampling was based on bullet entry points in carcasses. See also Ben‐Ami D, Boom K, Boronyak L, Croft D, Ramp D, Townend C, The ends and means of the commercial kangaroo industry: an ecological, legal and comparative analysis (THINKK, UTS, 2011) 3, 16-17.

- Keely Boom, Dror Ben-Ami, Louise Boronyak and Sophie Riley, ‘The Role of Inspections in the Commercial Kangaroo Industry’ (2013) 2 International Journal of Rural Law and Policy 1, 18.

- See Ben-Ami D, Boom K, Boronyak L, Townend C, Ramp D, Croft D and Bekoff M, ‘The welfare ethics of the commercial killing of free ranging kangaroos: an evaluation of the benefits and costs of the industry’ (2014) 23(1) Animal Welfare 1, 5. This estimation is based on ecological data and national commercial kill statistics for the period 2000-2009. This does not include the joeys killed as a consequence of non-commercial shooting. The numbers of joeys killed or left to die are not recorded. Accordingly, the figures are a 10-year projection based on the authors’ calculations (methods outlined in the article) and the national commercial kill statistics provided by the Commonwealth Government Department of Sustainability, Environment, Population and Communities in 2010.