Over the past week, in response to two shark attacks, six sharks have been caught on baited hooks and shot as part of the Queensland Government’s Shark Control Program. There is no conclusive evidence that culling sharks makes swimmers any safer. Instead, this reaction from government is yet another example of a willingness to immediately roll-back protection for wildlife in lieu of thoughtful, long-lasting action.

Shark attacks are clearly extremely traumatic, and our thoughts are with the victims of these tragedies. However the random, almost tit for tat, killing of sharks is not a solution and will do nothing to protect the average ocean-goer. It is instead a knee-jerk reaction to indicate action and placate the general public.

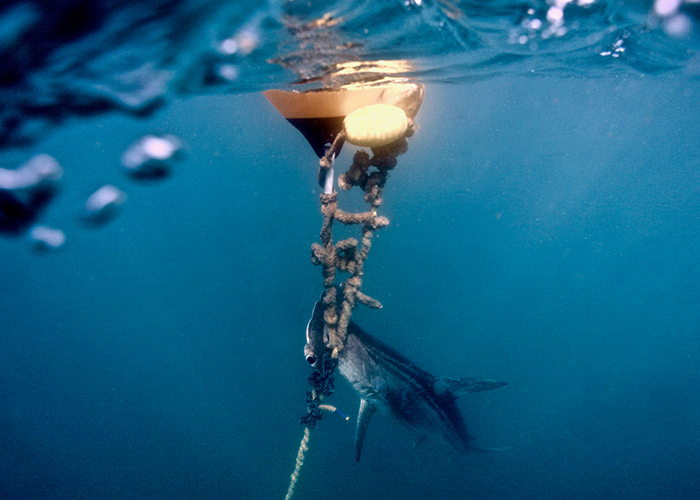

A scalloped hammerhead found dead on a drum line off Magnetic Island earlier this year. Photo: HSI/AMCS/N McLachlan

Placing baited hooks in the ocean to catch sharks isn’t new. Queensland has had drum lines and shark nets in the water since the sixties. The drum lines are designed to catch ‘dangerous’ sharks over 3 metres in length, including Bull and Tiger sharks. In 2017-18, more than 230 sharks were caught on drum lines in Queensland. Of these, 74 were ‘non-dangerous’ species, including two green sea turtles and an endangered scalloped hammerhead shark. Over the past 17 years, 97% of the 10,480 sharks that have been caught on drum lines have been at some level of conservation risk.

Humans are responsible for the death of more than one hundred million sharks globally every year. Sharks are responsible for around four deaths annually – worldwide. We know we are much more likely to be injured by a coconut or drink vending machine — even simply being left-handed is statistically more dangerous — yet ninety percent of shark populations around the globe have been exterminated.

Sharks are apex predators that have been swimming through our oceans for millions of years. Removing such an important element of the food chain would be irretrievably detrimental to the oceanic ecosystem, with the real potential to result in its total collapse. Sharks are the clean-up task force of our oceans, keeping populations of fish and other marine life in check. For a healthy ocean — an ocean rich in biodiversity — sharks are essential.

Shark culling programs have a track record of failure.

Between 1959 and 1976, Hawaii culled just under 5,000 sharks. The number of attacks remained the same. Three shark attacks in the space of three years led Western Australia to start a trial cull of a species protected under international, federal and state law; the Great White Shark. Unfortunately, baited hooks are unable to distinguish between species and instead of capturing this critically endangered animal, 172 non-target species met their end. The program cost Australian taxpayers $1.3 million.

Such government funded treatment of a protected shark is not unique to this species. Our governments continue to roll back protection for native and threatened animals in response to perceived benefit to humans.

In Western Australia, the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 allows the relevant minister to determine if a species status is listed as native. Recently, the Dingo, a species that has been roaming Australia for more than 5000 years, was stripped of its native status. By changing their legal status, current obligations for developing appropriate management plans can be abolished. This opens the door to an escalation of lethal control methods, instead of investment of resources into non-lethal alternatives to help ensure proper management of the population.

While we can’t compare dingoes to sharks as animals, we can compare government’s response to each of them. Both situations demonstrate a lack of understanding of how ecosystems function, and a general disrespect for Australian wildlife. If we can simply strip a species of its status or its legal protection on an apparent whim, how can we ever ensure the continued conservation of the species?

As technology advances, so too does the way we can protect people from potential shark attacks. Initiatives such as helicopter patrols, tagging and tracking sharks, and even shark-deterring wetsuits are exciting initiatives becoming more and more readily available. The eco shark barrier is a solid barrier that marine life cannot become entangled in. Shark Spotters keep a watchful eye over surfers and swimmers, using flags and alarms to alert people of sharks in the area. There are SMART versions of drumlines that allow sharks to be tagged and released. Aerial surveys and drones are being trailed as a way to keep swimmers safe. We can also invest more resources into professional patrols, education and surf lifesaving.

Knee-jerk reactions and more culling is really not the solution now or in the long term. Policy driven by fear and panic will not protect swimmers or sharks — an approach based on science and research will.

What you can do to help:

- Download the Australian Surfing guide to sharks. Read and share it with your friends and family who hang out in the ocean.

- Contact your local MP and let them know you support non-lethal alternatives to shark culling.

- Sign the petition calling for an end to lethal shark management programs.

- Learn about the Centre for Compassionate Conservation, an innovative research, education and advisory centre that improves the welfare of wild animals using a Compassionate Conservation approach.

Voiceless Blog Terms and Conditions: The opinions expressed on the Voiceless Blog are those of the relevant contributors and may not necessarily represent the views of Voiceless. Reliance upon any content, opinion, representation or statement contained in the article is at the sole risk of the reader. Voiceless Blog articles are protected by copyright and no part should be reproduced in any form without the prior consent of Voiceless.