Over 10 million layer hens are housed in intensive battery cage systems in Australia. These outdated and inadequate cages have been banned, or are being phased out, in a number of global markets including most member states of the European Union, New Zealand and Switzerland. For the first time, Australia is now on the brink of banning battery cages, acknowledging the significant and inherent risks they pose to the health and welfare of hens. Read more below about the issues with all systems of egg production, and how you can help achieve an end to the use of battery cages in Australia.

Permanent confinement

Battery cages are used on factory farms to confine egg-laying hens. Despite increasing community awareness about their plight, the vast majority of egg-laying hens are permanently warehoused with tens of thousands of other birds until their slaughter.

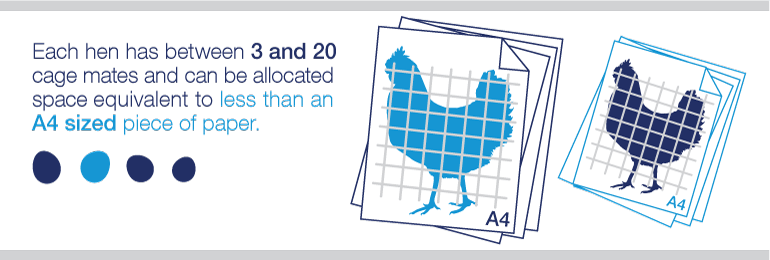

Hens in battery cages spend their lives in artificially lit surroundings designed to maximise laying activity.1 Each hen has anywhere between 3 and 20 cage mates.2 Depending on their body size, the number of hens per cage, or in which jurisdiction they reside, each hen can be allocated space less than that of an A4 sized piece of paper.3 This is insufficient room to act on natural instincts and behaviours like wing flapping, grooming, preening, stretching, foraging and dust bathing.4

According to animal welfare expert Dr John Webster, “the unenriched battery cage simply does not meet the physiological and behavioural requirements of the laying hen, which makes any quibbling about minimum requirements for floor space superfluous”.5

Although nesting is a behavioural priority for a hen, hens are unable to lay eggs in a discrete, private or enclosed nesting space when they are kept in conventional battery cages.6 Hens housed in battery cages have been found to display agitated pacing and escape behaviours which can last for up to four hours prior to laying their eggs.7 Ian Duncan, Emeritus Chair in Animal Welfare at the University of Guelph, states that the most significant source of battery hen frustration is “undoubtedly the lack of nesting opportunity.”8

Battery hens may also experience chronic pain from the development of lesions and foot problems, as a result of standing on often sloping wire floors that are designed to facilitate egg collection.9 Extreme inactivity also results in hens developing disuse osteoporosis, leading to chronic pain from bone fractures.10

Debeaking

Due to the suppression of many of their natural instincts and social interactions, such as choosing a suitable nesting place to lay their eggs, hens raised in battery cages can become frustrated, fearful and aggressive. This may trigger behaviours such as hen pecking, bullying and cannibalism.11

Evidence suggests that battery hens have insufficient room to maintain a normal ‘personal space’ and to escape from bullying by companions. Physiological stress levels are also higher in birds subject to spatial restriction.12

In an attempt to prevent this behaviour from causing injuries to other hens, producers routinely conduct beak-trimming or ‘debeaking’ on chicks.13 This most commonly involves the amputation or searing off of a portion of the upper and lower beak using an electrically heated blade.14 Re-trimming may also be carried out if a hen’s beak grows back.15

Debeaking causes tissue damage and nerve injury, particularly in older birds. In addition to the pain caused during and immediately following amputation, scientists believe the process can cause the beak to develop long-lasting and painful neuromas or tumours, which deter hens from using their beaks to forage or exhibit other natural behaviours.16

In Australia, the ACT is the only jurisdiction to have outlawed the practice of debeaking.17 In other Australian jurisdictions, debeaking is permitted to be performed as a matter of routine without pain relief.18

Male chicks

One of the most unknown aspects of egg production for all production systems (including free range) is the mass slaughter of male chicks. As males are not able to lay eggs and have not been selectively bred for their size or meat quality, male chicks are generally considered unsuitable for meat production, and accordingly, are slaughtered following hatching.

The permitted methods of slaughter include carbon dioxide gassing or maceration (grinding of live chicks).19 As many as 10 million male chicks are killed this way each year.20

Sentience

These practices ignore the research which demonstrates that chickens have preferences, particularly in terms of the environment in which they are kept, and experience physical sensations and emotional responses such as pain, fear, anxiety, pleasure and enjoyment.21 Studies have also shown that chickens are highly social animals with complex cognitive abilities.22

Despite this, battery hens are afforded little protection under the Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals: Domestic Poultry (4th Edition) (the Poultry Code) or State and Territory animal welfare laws, which permit permanent confinement and debeaking.

Law reform

The ACT is the only jurisdiction in Australia to have completely prohibited the use of battery cages,23 with Tasmania prohibiting any new battery hen operators from 2013.24

Overseas, the European Union (EU) legislated to phase out battery cages by 2012,25 with the UK having met this target and the European Commission threatening non-compliant member countries with legal action.26

In 1981, Switzerland established new requirements for the housing of chickens which came into effect in 1991, effectively eliminating battery cages in Switzerland and making aviaries the most common method of raising hens.27

Eight US states have implemented bans on the use of battery cages for egg production.

Consumer attitudes

Over the last decade, Australian consumers have increasingly embraced the global ethical food movement. A 2014 Voiceless national survey of 1,041 adult Australians found 61% of respondents have bought ‘free range’ or ‘humanely’ derived animal products on animal welfare grounds. This is consistent with a 2011 Voiceless study, which found 80% of individuals supported a battery cage ban.

Help end battery cages in Australia

State and territory governments are currently in the process of considering whether to phase out the use of battery cages for egg production in Australia. Agriculture Ministers are deciding on the Australian Animal Welfare Standards and Guidelines for Poultry, and have the power to ban battery cages forever.

The new Standards and Guidelines will replace the outdated Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals Domestic Poultry which permits the use of battery cages despite overwhelming public concern. Research has found that 3 in 4 Australians are concerned about the welfare of battery-caged hens, and 8 in 10 want to see battery cages phased out. Although Voiceless believes that all hens should be free from exploitation and systems of industrialised factory farming, this is an opportunity to make history and set the bar higher for over 10 million hens confined in cramped barren cages.

If you support a phase-out, find out who your local MP is and reach out to let them know what you think. All the information you need is outlined below in Voiceless’s comprehensive report exploring hen welfare in the Australian egg industry.

Learn more

- Access a detailed list of resources exploring factory farming and the law in Australia here.

- Read and share Voiceless’s ‘Briefing on hen welfare in the Australian egg industry‘, which provides an overview of facts about the Australian egg industry and the key welfare issues for hens and their chicks.

- For more in-depth information, see our report: ‘Unscrambled: The hidden truth of hen welfare in the Australian egg industry‘, which provides a greater insight into hen suffering and assesses the key animal protection issues with the use of battery cages, barn-laid and free range systems from an animal welfare and scientific perspective. You can flip through the report below.

Last updated July 2021

- Tina Widowski et al, ‘Part 1: Overview Of International Egg Production, Hen Housing and Animal Welfare Standards’ in Welfare Issues and Housing for Laying Hens: International Developments and Perspectives <http://www.aph.gov.au/~/media/Estimates/Live/rrat_ctte/estimates/bud_1213/daff/5_aecl_c.ashx>; Primary Industries Standing Committee, Model Code of Practice for the Welfare of Animals- Poultry (4th Edition) (2002) (‘the Poultry Code’), paragraph 5.

- Dr David Witcombe, ‘Layer hen welfare: a challenging and complex issue’ (Speech delivered at Animal Welfare Science Centre, Department of Primary Industries, Atwood, Victoria, 8 June 2007) <http://www.animalwelfare.net.au/article/scientific-seminars>. See also Tina M. Widowski et al, ibid: “The number of hens housed in a conventional cage can vary with size of the cage and space allowance provided, but generally ranges from 3 to 7 birds.”

- The permitted stocking densities differ in each State and Territory, and depending on the weight of the hens and the number of hens crammed into one cage. In NSW, for example, if the average weight of the hen in the cage is less than 2.4 kilograms, she will be permitted a space of around 550 cm2: Regulation 10(5)(a), Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Regulation 2012 (NSW). An A4 sheet of paper, with sides of 21.0 cm x 29.7 cm, has an area of 623.7 cm2.

- Dr John Webster, Animal Welfare: Limping towards Eden (2005, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford), 121; Bernie E Rollin, Farm Animal Welfare: Social, Bioethical, and Research Issues (1995, Iowa State Press, Iowa), 120; Michael C Appleby et al, Poultry Behaviour and Welfare (2004, CABI Publishing, Wallingford), 46.

- Webster (2005), ibid, 120.

- LayWel Project, ‘Welfare implications of changes in production systems for laying hens’ (2004, University of Bristol <http://www.laywel.eu/web/pdf/deliverable%2071%20welfare%20assessment.pdf>; J Mench, ‘The welfare of poultry in modern production systems’ Poultry Science Review (1992) 4, 112; K Lorenz, ‘Animals are sentient beings: Konrad Lorenz on instinct and modern factory farming’ Der Spiegel (November 17, 1980) 34(47), 264; Ian Duncan, “The pros and cons of cages”, World’s Poultry Science Journal (2001) 57(4), 381-90.

- Mench (1992), ibid.

- Duncan (2001), n 6, 385.

- R Tauson, ‘Health and production in improved cage designs’, Poultry Science (1998), 77, 1820–1827; Michael C Appleby, ‘Do Hens Suffer in Battery Cages?’, Compassion in World Farming (October 1991), <http://www.ciwf.org.uk/includes/documents/cm_docs/2008/d/do_hens_suffer_in_battery_cages_1991.pdf>; Rollin (1995), p 126; Duncan (2001), n 6, 387.

- Webster (2005), n 4, 121; Duncan (2001), n 6.

- Dr Lesley Rogers, The development of brain and behaviour in chicken (1995, CABI Publishing, Wallingford), 219; Philip Glatz et al, ‘Beak Trimming Training Manual’ Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC) (2002), 1 <http://www.aecl.org/assets/RD-files/Outputs-2/SAR-35AA-FInal-Report.pdf>.

- LayWel Project, n 6.

- Poultry CRC, ‘Beak trimming’, Poultry Hub <http://www.poultryhub.org/health/health-management/beak-trimming/>.

- Poultry CRC, ibid. Continuing welfare concerns regarding the use of a hot blade for beak trimming has prompted research into the development of alternative methods including laser trimming. See: Philip Glatz, Laser Beak Trimming; A report for Australian Egg Corporation Limited (July 2004) <http://www.aecl.org/assets/RD-files/Outputs-2/SAR-45AA-Final-Report.pdf>.

- Poultry CRC, n 13.

- B O Hughes and M J Gentle, ‘Beak trimming of poultry – its implications for welfare’ (1995) Worlds Poultry Science Journal 51, 51-61; Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC), ‘Opinion on Beak Trimming of Layer Hens’ (November 2007) <http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20121007104210/http://www.fawc.org.uk/pdf/beak-trimming.pdf>.

- Animal Welfare Act 1992 (ACT), s 9C.

- Poultry Code, paragraph 13.2; Animal Welfare Act (NT), s 79 (compliance with the Poultry Code is a defence); Animal Welfare Act 2002 (WA), s 25 (compliance with the Poultry Code is a defence); Animal Welfare Act 1985 (SA), s 43 (compliance with the Poultry Code is a defence); Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986 (VIC), s 11(2) (compliance with the Poultry Code is a defence); Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1979 (NSW), s 34A(3) (compliance with the Poultry Code can be admitted as evidence of compliance with the Act). In Tasmania, the Poultry Code is advisory in nature and the Animal Welfare Act 1993 (TAS) silent on the issue of de-beaking.

- Poultry Code, paragraph 14.1.

- There is limited data available on the number of male chicks slaughtered each year as part of Australian egg production. The 10 million figure is based on the number of battery hens kept in Australian cage systems each year.

- Michael C Appleby et al, Poultry Behaviour and Welfare (2004, CABI Publishing, Cambridge), 130-142; R B Jones, ‘Environmental enrichment: the need for practical strategies to improve poultry welfare’ in G C Perry (ed), Welfare of the Laying Hen (2004, CABI Publishing, Cambridge, MA), 216; Rogers (1995), n 11, 219.

- Rogers (1995), n 11, 219; Carolynn L Smith And Sarah L Zielinksi, ‘The startling intelligence of the common chicken’, Scientific American (2014) 310(2).

- Animal Welfare Act 1992 (ACT), s 9A.

- Animal Welfare (Domestic Poultry) Regulations 2013 (TAS), r 5.

- In 1999 the EU agreed a Directive on Laying Hens (1999/74/EC) that resulted in the banning of the barren battery cage (enriched cages are still permitted to be used). Producers were given a 12 year phase-out period, bringing the ban into effect on 1 January 2012.

- FarmingUK, ‘Italy and Greece to face European Court on battery cage ban’ (26 April 2013) <https://www.farminguk.com/news/italy-and-greece-to-face-european-court-on-battery-cage-ban_25426.html>.

- Bruce A Wagman and Matthew Liebman, A Worldview of Animal Law (2011, Carolina Academic Press, Carolina), p 69.